I recently finished the prototype for my third puzzle, The Core Cube. I played around with a couple of variations of this puzzle in SketchUp, and finally settled on the diagonal open feature on the sides of the cube with the "core cube" caged in the center. The puzzle consists of thirteen pieces that assemble into a 3"x3"x3" cube. I typically use red oak in many of my fine woodworking projects, but for this prototype I opted for inexpensive poplar. In hindsight, I should have just used red oak or mahogany; poplar is soft like white pine and prone to tear-out. I replaced the blade on my saw and used a zero-clearance jig I built to minimize this, but some defects are still evident on the small workpieces. I suppose that's why they're called prototypes. For future productions of this puzzle, I will be ripping down my own stock from mahogany, one of my favorite woods.

Saturday, April 4, 2015

Saturday, March 28, 2015

In-congruent Mini

The idea for In-congruent Mini was inspired by traditional tangram puzzles. I designed the puzzle pieces as different configurations of triangles with an alternating color pattern. I then designed twelve different patterns that could be made with the five puzzle pieces in a vector drawing program. Finally, I printed the pages, trimmed them, and affixed them with spray adhesive to art boards.

|

| Puzzle pieces with finished puzzle board |

|

| The goal is to recreate the patterns filling the white voids with the red colored triangles |

|

| It can be harder than it looks |

Saturday, March 21, 2015

The Asterisk

I'd never designed or made a puzzle before now... ever. I admired the work and craftsmanship of puzzle designers for a number of years, and recently I decided to construct some of my own puzzle creations. There is something very exciting and satisfying about coming up with an idea and making that object with your own hands; I enjoy wood working, and puzzles have become an extension of that passion.

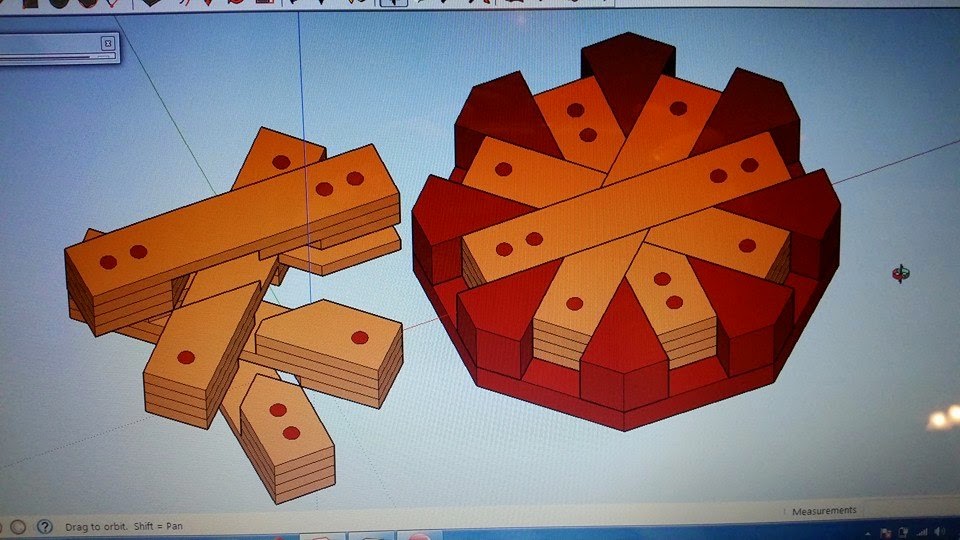

The Asterisk was my first attempt at designing and making a puzzle. I was happy with the concept: arrange 28 angled puzzle pieces in 4 layers to form the 8 sided asterisk pattern in four separate challenges. The first challenge is the simplest, assemble the puzzle with an all black 2 dot pattern. The second challenge is to assemble the puzzle with all red alternating 1 and 2 dot pattern. The third challenge is to assemble the puzzle with alternating red 1 dot and black 2 dot pattern. The fourth and most difficult challenge is to assemble the puzzle alternating a red 2 dot and black 2 dot pattern; if you don't plan your moves and assemble it with the right pieces, you will reach the last layer with the incorrect colored or numbered pieces.

The first thing I learned in my puzzle creation journey is that puzzle making typically involves very small work pieces that tools like table and miter saws aren't designed for. Attempting to position and hold anything less than 6 inches on a compound miter saw is a good way to remove some of those pesky fingers you may be trying to get rid of. Of course I'm joking, but the point is very serious; manipulating small work pieces on dangerous power tools without carefully planning and building proper jigs can lead to serious injury.

The second thing I learned is that tolerances are much more precise in puzzles than in other projects I've done; forget about sixteenths of an inch, to get my puzzle to fit together properly I needed precision on the order of thousandths of an inch. I myself having no background in mechanical engineering had no idea how to achieve this level of precision; needless to say my scrap bin is full of 'tiny failures'. Many articles I read showed preference for using the metric system of measurement, I prefer decimal inches for a couple of reasons: firstly, I've used fractional inches my entire life and I have a 'mental ruler' of sorts, a sense of scale that matches the English system of measurement. Lastly, I live in the United States where the materials and tools that I purchase are all sold in the English system of measurement and I'm simply far too lazy to use my conversion calculator every time I go to the hardware store.

Compound error is a craftsman's bane, and like many amateurs I turned to YouTube for help, there I learned to build better jigs and to set precise blade distances with a pair of digital calipers and a micrometer. Lo and behold, it worked! I even learned to repeat the process and turned out two puzzles in a weekend. The whole endeavor, while difficult and frustrating at times turned out to be extremely rewarding. I have a number of new and unique puzzles on the drawing board, and I can't wait to make them!

The Asterisk was my first attempt at designing and making a puzzle. I was happy with the concept: arrange 28 angled puzzle pieces in 4 layers to form the 8 sided asterisk pattern in four separate challenges. The first challenge is the simplest, assemble the puzzle with an all black 2 dot pattern. The second challenge is to assemble the puzzle with all red alternating 1 and 2 dot pattern. The third challenge is to assemble the puzzle with alternating red 1 dot and black 2 dot pattern. The fourth and most difficult challenge is to assemble the puzzle alternating a red 2 dot and black 2 dot pattern; if you don't plan your moves and assemble it with the right pieces, you will reach the last layer with the incorrect colored or numbered pieces.

The first thing I learned in my puzzle creation journey is that puzzle making typically involves very small work pieces that tools like table and miter saws aren't designed for. Attempting to position and hold anything less than 6 inches on a compound miter saw is a good way to remove some of those pesky fingers you may be trying to get rid of. Of course I'm joking, but the point is very serious; manipulating small work pieces on dangerous power tools without carefully planning and building proper jigs can lead to serious injury.

The second thing I learned is that tolerances are much more precise in puzzles than in other projects I've done; forget about sixteenths of an inch, to get my puzzle to fit together properly I needed precision on the order of thousandths of an inch. I myself having no background in mechanical engineering had no idea how to achieve this level of precision; needless to say my scrap bin is full of 'tiny failures'. Many articles I read showed preference for using the metric system of measurement, I prefer decimal inches for a couple of reasons: firstly, I've used fractional inches my entire life and I have a 'mental ruler' of sorts, a sense of scale that matches the English system of measurement. Lastly, I live in the United States where the materials and tools that I purchase are all sold in the English system of measurement and I'm simply far too lazy to use my conversion calculator every time I go to the hardware store.

Compound error is a craftsman's bane, and like many amateurs I turned to YouTube for help, there I learned to build better jigs and to set precise blade distances with a pair of digital calipers and a micrometer. Lo and behold, it worked! I even learned to repeat the process and turned out two puzzles in a weekend. The whole endeavor, while difficult and frustrating at times turned out to be extremely rewarding. I have a number of new and unique puzzles on the drawing board, and I can't wait to make them!

|

| 3D model designed with Google SketchUp |

|

| The pieces cut precisely and numbered divots drilled in |

|

| Sanded and stained red oak puzzle pieces |

|

| The finished puzzle with tray |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)